8 Optimization of

continuum structures

In the previous chapter, we learned how to transform a continuous

elastic problem defined on a two-dimensional domain into a discrete

problem using finite elements. Now we want to optimize such

problems.

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter and finishing the exercise, you should be

able to

transfer solution methods from intrinsically discrete truss

structures to FEM-discretized problems

explain the solution process for variable thickness sheets (size

optimization)

solve for binary topologies using the SIMP approach

discuss numerical problems in topology optimization

apply filters to deal with numerical problems and manufacturing

constraints in topology optimization

explain the need for mesh morphing in shape optimization

8.1 Size optimization

Let’s consider a two-dimensional domain discretized with finite

elements, in which we can adjust the thickness of each element. We may

seek the best distribution of thicknesses \(\mathbf{d}\) to minimize compliance \(C\) with a constrained amount of material

volume \(V_0\). This problem can be

formulated in analogy to the standard problem of sizing optimization

stated in Equation

\[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\mathbf{d}} \quad & C(\mathbf{d}) = \mathbf{f} \cdot

\mathbf{u}(\mathbf{d})\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & \mathbf{d} \cdot \mathbf{A} - V_0 \le

0 \\

& \mathbf{d} \in \mathcal{D}\\

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:sheet_optimization}{\qquad(8.1)}\] where \(\mathbf{A}\) denotes the area of an

element. Mathematically, this problem is equivalent to the truss problem

and can be solved in the same way: We formulate the Lagrangian \[\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{d}, \mu) = C(\mathbf{d}) +

\mu \left( \mathbf{d} \cdot \mathbf{A} - V_0 \right)

\label{eq:lagrangian_sheet_optimization}{\qquad(8.2)}\] and

determine its derivative \[\frac{\partial

\mathcal{L} (\mathbf{d}, \mu)}{\partial d_j}

= \frac{\partial C(\mathbf{d})}{\partial d_j} + \mu

A_j{\qquad(8.3)}\] with \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial d_j} = -

\mathbf{u}_j(\mathbf{d}) \cdot \mathbf{k}^0_j \cdot

\mathbf{u}_j(\mathbf{d}) = -2w_j(\mathbf{d}).

\label{eq:sensitivity_sheet}{\qquad(8.4)}\] In comparison to

Equation for trusses with four degrees of freedom, the element

displacement vector contains eight degrees of freedom for these 2D

problems with linear quad elements (\(\mathbf{u}_j \in \mathcal{R}^8, \mathbf{k}^0_j \in

\mathcal{R}^{8\times 8}\)).

Just like the truss problem, the variable thickness sheet problem can

be approximated using MMA with lower asymptotes only. Subsequently, it

is solved with the dual method and a line search to find the Lagrange

parameter \(\mu\). The entire procedure

is identical to Section , if we replace the truss cross sections \(\mathbf{a}\) with element thicknesses \(\mathbf{d}\) and the truss lengths \(\mathbf{l}\) with element areas \(\mathbf{A}\).

Example: Size optimization with

MMA

Consider a FEM cantilever beam from the previous example. Instead of

just computing the displacements, we are now interested in finding the

optimal thickness of each element given a volume constraint.

We formulate the following algorithm to solve that problem:

Define the cantilever FEM model with all nodes \(\mathcal{N}\), elements \(\mathcal{E}\), material property \(E\), volume constraint \(V_0\), design limits \(\mathbf{d}^-, \mathbf{d}^+\) and the

initial design choice \(\mathbf{d}^0\).

Compute the displacements \(\mathbf{u}^k = \mathbf{u}(\mathbf{d}^k)\)

by solving the FEM system for the current design \(\mathbf{d}^k\).

Compute the strain energies densities for all elements using the

previously computed displacements \[w^k_j(\mathbf{d}^k) =

\frac{1}{2}\mathbf{u}^k_j \cdot \mathbf{k}^0_j \cdot

\mathbf{u}^k_j{\qquad(8.5)}\]

Compute the lower asymptotes as \(\mathbf{L}^k =\mathbf{d}^k - s (\mathbf{d}^+ -

\mathbf{d}^-)\) with \(s \in

(0,1)\) during the first two iterations and according to \[L^k_j =

\begin{cases}

d^k_j - s (d^{k-1}_j-L^{k-1}_j) &

(d_j^k-d_j^{k-1})(d_j^{k-1}-d_j^{k-2}) < 0\\

d^k_j - \frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (d^{k-1}_j-L^{k-1}_j) &

\text{else}

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.6)}\] in the following

iterations.

Compute the lower move limit as \[\tilde{\mathbf{d}}^{-,k} =

\max(\mathbf{d}^-, 0.9 \mathbf{L}^k + 0.1

\mathbf{d}^k){\qquad(8.7)}\]

Evaluate the analytical solution \[\begin{aligned}

\hat{d}_j(\mu) &= L_j^k + \sqrt{\frac{2 w_j

(\mathbf{d}^k)

(L^k_j-d^k_j)^2}{\mu A_j}} {\qquad(8.8)}\\

\mathbf{d}^* (\mu) &=

\textrm{clamp}\left(\hat{\mathbf{d}}(\mu), \tilde{\mathbf{d}}^{-,k},

\mathbf{d}^+ \right)

{\qquad(8.9)}\end{aligned}\]

Perform a line search to find the root \(\mu^*>0\) in \[\frac{\partial \underline{\mathcal{L}}}{\partial

\mu}(\mu) = \mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{d}^* (\mu) - V_0 =

0{\qquad(8.10)}\] with Newton’s method or bisection

method.

Repeat with steps 2-7 until convergence or a maximum number of

iterations is reached.

The following image shows a result of the algorithm for the

cantilever problem stated above. Black areas use the full maximum

thickness \(\mathbf{d}^+\) and white

areas use the minimum thickness \(\mathbf{d}^-\). The intermediate values are

represented by different shades of gray.

8.2 Topology optimization with

MMA

In a topology optimization of continuum structures, we want to

optimize the neighborhood relations of a structure. While the size or

shape of an object could be changed by some deformation, we cannot

change a topology to another by a "rubber-like" deformation. Essentially

this means, in topology optimization we are seeking the fundamental

structure of a component: Which parts are connected? How many holes are

in it?

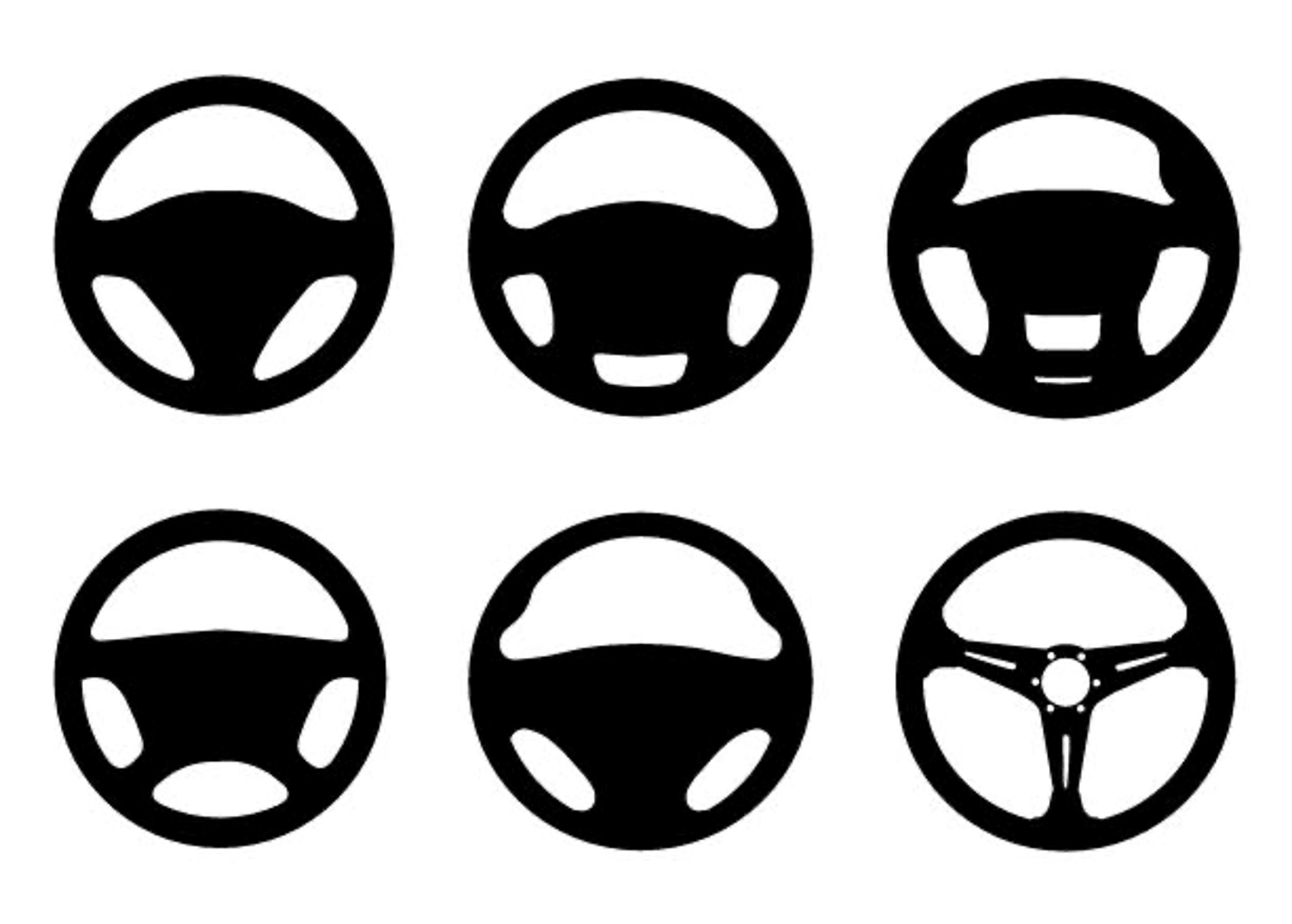

Example: Topology of steering

wheels

Out of the following schematic steering wheels, the top left wheel may

be transformed to the bottom center wheel by an appropriate deformation.

They have the same topology, but different shapes. However, they cannot

be transformed to any other steering wheel, as this would require

formation of new holes and break the neighborhood relations.

There are two main approaches to optimize the topology (Eschenauer and Olhoff

2001): In a geometry-based formulation, we describe the

domain in a dynamic fashion ( e.g. by a Level-Set method) and modify

this geometry towards the optimum (e.g. by empirical growth rules like

SKO or CAIO). In a material-based formulation, we describe the

entire domain with finite elements and then seek a material distribution

where each element is either completely filled or completely unfilled

with material. In this lecture, we focus entirely on the latter

approach.

We can formulate such a problem by reinterpreting the thickness

variable as a normalized material density \(\pmb{\rho}\), where \(\rho_j=1\) indicates presence of material

and \(\rho_j=0\) indicates absence of

material in element \(j\). The

stiffness of each element becomes a function of \(\rho_j\), e.g. \[\mathbb{C}(\rho_j)=

\begin{cases}

\mathbb{C} & \text{if} \quad \rho_j = 1 \\

0 & \text{if} \quad \rho_j = 0

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.11)}\]

Then, the problem statement reads \[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\pmb{\rho}} \quad & C(\pmb{\rho}) = \mathbf{f} \cdot

\mathbf{u}(\pmb{\rho})\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & \pmb{\rho} \cdot \mathbf{V} - V_0 \le

0 \\

& \rho_j \in \{0, 1\}\\

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:topology_optimization}{\qquad(8.12)}\]

where the only change compared to Equation 8.1 is the discrete nature of the

design variables \(\pmb{\rho}\) and the

name of the design variables.

As mentioned during truss optimization, the binary problem is

notoriously hard to solve. Hence we use Solid Isotropic Material

with Penalization (SIMP) again, which is denoted as \[\mathbb{C}(\rho_j)= \rho_j^p

\mathbb{C}{\qquad(8.13)}\] for the generalized FEM problem.

Incorporating the SIMP method to the optimization is

straight-forward: The element stiffness for a 2D problem with element

thicknesses \(d_j\) is now \[\mathbf{k}_j(\rho_j) = \rho_j^p d_j

\mathbf{k}^0_j{\qquad(8.14)}\] and consequently, the gradient

becomes \[\frac{\partial\mathbf{k}_j(\rho_j)}{\partial

\rho_j} = p \rho_j^{p-1} d_j\mathbf{k}^0_j.{\qquad(8.15)}\]

Then, we just need to adjust the sensitivity (see Equation 8.4) slightly towards \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial \rho_j} (\pmb{\rho}) =

- p \rho_j^{p-1} d_j\mathbf{u}_j(\pmb{\rho}) \cdot \mathbf{k}^0_j \cdot

\mathbf{u}_j(\pmb{\rho}) = -2 p \rho_j^{p-1} d_j w_j(\pmb{\rho}).

\label{eq:sensitivity_topology}{\qquad(8.16)}\]

Example: Topology optimization with MMA and

SIMP

Consider the FEM cantilever beam from the previous example. We slightly

change the algorithm towards the following:

Define the cantilever FEM model with all nodes \(\mathcal{N}\), elements \(\mathcal{E}\), material property \(E\), volume constraint \(V_0\), a lower design limit \(\pmb{\rho}^-\) and the initial design

choice \(\pmb{\rho}^0\).

Compute the displacements \(\mathbf{u}^k = \mathbf{u}(\pmb{\rho}^k)\)

by solving the FEM system for the current design \(\pmb{\rho}^k\).

Compute the strain energies densities for all elements using the

previously computed displacements \[w^k_j(\pmb{\rho}^k) = \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{u}^k_j

\cdot \mathbf{k}^0_j \cdot

\mathbf{u}^k_j{\qquad(8.17)}\]

Compute the lower asymptotes as \(\mathbf{L}^k =\pmb{\rho}^k - s (\mathbf{1} -

\pmb{\rho}^-)\) with \(s \in

(0,1)\) during the first two iterations and according to \[L^k_j =

\begin{cases}

\rho^k_j - s (\rho^{k-1}_j-L^{k-1}_j) &

(\rho_j^k-\rho_j^{k-1})(\rho_j^{k-1}-\rho_j^{k-2}) < 0\\

\rho^k_j - \frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (\rho^{k-1}_j-L^{k-1}_j)

& \text{else}

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.18)}\] in the following

iterations.

Compute the lower move limit as \[\tilde{\pmb{\rho}}^{-,k} =

\max(\pmb{\rho}^-, 0.9 \mathbf{L}^k + 0.1

\pmb{\rho}^k){\qquad(8.19)}\]

Evaluate the analytical solution \[\begin{aligned}

\hat{\rho}_j(\mu) &= L_j^k + \sqrt{\frac{2 p

\rho_j^{p-1} d_j w_j (\pmb{\rho}^k)

(L^k_j-d^k_j)^2}{\mu V_j}} {\qquad(8.20)}\\

\pmb{\rho}^* (\mu) &=

\textrm{clamp}\left(\hat{\pmb{\rho}}(\mu), \tilde{\pmb{\rho}}^{-,k},

\mathbf{1}\right)

{\qquad(8.21)}\end{aligned}\]

Perform a line search to find the root \(\mu^*>0\) in \[\frac{\partial \underline{\mathcal{L}}}{\partial

\mu}(\mu) = \mathbf{V} \cdot \pmb{\rho}^* (\mu) - V_0 =

0{\qquad(8.22)}\] with Newton’s method or bisection

method.

Repeat with steps 2-7 until convergence or a maximum number of

iterations is reached.

This procedure results in the following solution:

Obviously, the SIMP approach helps us to find a binary solution of

the discretized problem stated in Equation 8.12. However, we may ask ourselves

if there is a unique solution to this problem independent of

discretization. And it turns out, the answer is no: You can improve any

given design by replacing it with finer structures in a process that

goes on indefinitely (Christensen and Klarbring 2008). In

addition to the theoretical non-existence of a solution, this also means

that our solution is mesh-dependent: If we want to refine the

solution, we may end up with a totally different solution.

Even if we were to accept mesh dependence and the theoretical problem

of ill-posedness, we are still left with challenges in the resulting

designs. First of all, fine structures may be hard to manufacture. Even

additive manufacturing methods are limited to some minimal structure

size. Secondly, we may observe checkerboard-like patterns on the

structure. These are numerical artifacts from the fact that we use

linear shape functions which lead to an overestimation of the stiffness

for that configuration.

Example: Mesh dependency

We can increase the resolution of the previous examples to achieve

better compliance results. However, this demonstrates the

mesh-dependence of the solution as we observe different structures in

both cases. Additionally, the resulting fine structures might be

difficult to manufacture.

We can address all these problems with the introduction of filters as

a regularization (Harzheim 2014; Lazarov and

Sigmund 2011). There are two traditional approaches for

mesh-independent filtering: density filtering and

sensitivity filtering. In density filtering, we replace the

density \(\pmb{\rho}\) with a weighted

sum of neighboring densities, and use this filtered density \(\tilde{\pmb{\rho}}\) in the stiffness

evaluation \[\mathbb{C}(\rho_j)=

\tilde{\rho}_j^p \mathbb{C}.{\qquad(8.23)}\] The filtered density

is computed according to \[\tilde{\rho}_j

(\pmb{\rho}) = \frac{\sum_i H_{ji} A_i \rho_i}{\sum_i H_{ji}

A_i}{\qquad(8.24)}\] with a distance weighting matrix \[H_{ji} =

\begin{cases}

R-\textrm{dist}(i,j) & \text{if} \quad \textrm{dist}(i,j)

\le R \\

0 & \text{else},

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.25)}\] where \(R\) describes the filter radius and \(\textrm{dist}(i,j)\) the distance between

element centers of elements \(i\) and

\(j\). This filter results in a

structural weakening of structures finer than \(R\), as they get smeared with neighboring

empty elements. Hence, the filter solves the mesh-dependency problem,

prevents structures that cannot be manufactured and prevents

checkerboard patterns. However, we need to account for the filter during

sensitivity computation by \[\frac{\partial

C}{\partial \rho_j}

= \frac{\partial C}{\partial \tilde{\rho}_m} \frac{\partial

\tilde{\rho}_m}{\partial \rho_j}

= \frac{\partial C}{\partial \tilde{\rho}_m} \frac{H_{jm} A_m

}{\sum_i H_{ji} A_i}{\qquad(8.26)}\] and in the volume

constraint.

An alternative to filtering densities is filtering of sensitivities.

We may compute the filtered sensitivity as \[\widetilde{\frac{\partial C}{\partial \rho_j}} =

\frac{A_j}{\rho_j} \frac{\sum_i H_{ji} \frac{\rho_i}{A_i} \frac{\partial

C}{\partial \rho_i}}{\sum_i H_{ji}}{\qquad(8.27)}\] which is a

purely heuristic concept, i.e. there is no mathematical proof for this

filter to work (Sigmund and Petersson 1998;

Sigmund 2007). However, we can implement this formulation simply

by replacing the sensitivities in 8.16 with filtered sensitivities.

This is very efficient, simple to implement and experience shows that

this filter works quite well.

Example: Sensitivity filtering

The following images show the optimized cantilever beams from previous

examples with enabled sensitivity filtering employing the same filtering

radius for each resolution. Filtering prevents small structures and

regularizes the problem such that we achieve the same optimal designs

for different mesh sizes.

There is one more challenge in the SIMP formulation of the standard

topology optimization problem: For \(p>1\), the problem is not convex anymore

and different starting points may result in different local minima (Christensen and Klarbring

2008). A strategy to cure termination at non-global minima is a

gradual increase of \(p\) starting from

\(p=1\) or using multiple starting

points.

8.3 Topology

optimization with optimality criteria

The solution via MMA is in line with the previous chapters of this

manuscript and is able to solve arbitrary problems beyond the compliance

minimization stated in problem 8.12. Historically, this specific

problem was first solved with the optimality criteria method

instead of convex approximations. The idea here is that we can use the

gradient of the Lagrangian \[\mathcal{L}(\pmb{\rho}, \mu) = C(\pmb{\rho}) +

\mu \left( \pmb{\rho} \cdot \mathbf{V} - V_0

\right),{\qquad(8.28)}\] which is \[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L} (\pmb{\rho},

\mu)}{\partial\rho_j}

= \frac{\partial C(\pmb{\rho})}{\partial \rho_j} + \mu V_j =

0,{\qquad(8.29)}\] at the optimal point, to formulate an

optimality condition \[G_j =

\frac{-\frac{\partial C(\pmb{\rho})}{\partial \rho_j}}{\mu V_j} =

\frac{p \rho_j^{p-1} d_j \mathbf{u}_j(\pmb{\rho}) \cdot \mathbf{k}^0_j

\cdot \mathbf{u}_j(\pmb{\rho})}{\mu V_j} = 1{\qquad(8.30)}\] that

must be fulfilled at the optimum whenever a variable does not reach its

bounds. A heuristic algorithm can now compute \(G_j\) and adjust \(\rho_j\) such that \(G_j\) approaches 1. We may realize that

increasing \(\rho_j\) increases the

stiffness and hence decreases the displacement for a given load.

Consequently, increasing \(\rho_j\)

decreases \(G_j\) and vice versa.

Hence, an update rule \[\hat{\rho}_j^{k+1} =

\left(G_j^k\right)^\xi \rho_j^k{\qquad(8.31)}\] drives the

solution towards the optimal point \(\rho_j^*\), where \(G^*_j=1\). The exponent \(\xi \in (0,1]\) stabilizes the algorithm

with typical values being \(\xi=0.5\)

(Harzheim

2014).

In addition, we employ move limits \[\begin{aligned}

\rho_j^{-,k} &= \max \left(\rho_j^-, (1-m)\rho_j^k \right)

{\qquad(8.32)}\\

\rho_j^{+,k} &= \min \left(\rho_j^+, (1+m)\rho_j^k \right)

{\qquad(8.33)}\end{aligned}\] to compute the next value as \[\rho_j^{k+1} = \textrm{clamp}

\left(\hat{\rho}_j^{k+1}, \rho_j^{-,k}, \rho_j^{+,k}

\right).{\qquad(8.34)}\] The move limits reduce the maximum step

width and account for bounds on the design variables.

To compute \(G_j\), we need to

determine the value of the Lagrange multiplier \(\mu\). For the compliance problem, we can

intuitively assume that the stiffest structure will use all material and

consequently, that the volume constraint will be active. The Lagrange

multiplier may be found with the bisection method on the feasibility

condition \[\frac{\partial

\mathcal{L}}{\partial \mu} = \pmb{\rho}(\mu) \cdot \mathbf{V} - V_0 =

0.{\qquad(8.35)}\]

Example: Algorithm with optimality

criteria

Consider a FEM cantilever beam from the previous example.

We formulate the following algorithm to solve that problem:

Define the cantilever FEM model with all nodes \(\mathcal{N}\), elements \(\mathcal{E}\), material property \(E\), volume constraint \(V_0\), lower design limit \(\pmb{\rho}^-\) and the initial design

choice \(\pmb{\rho}^0\).

Compute the displacements \(\mathbf{u}^k = \mathbf{u}(\pmb{\rho}^k)\)

by solving the FEM system for the current design \(\pmb{\rho}^k\).

Compute the sensitivity \[\frac{\partial C}{\partial \rho_j} = -2 p

\rho_j^{p-1} d_j w_j(\pmb{\rho}){\qquad(8.36)}\] and filter it

according to \[\widetilde{\frac{\partial

C}{\partial \rho_j}} = \frac{1}{\rho_j} \frac{\sum_i H_{ji} A_i \rho_i

\frac{\partial C}{\partial \rho_i} }{\sum_i H_{ji}

A_i}.{\qquad(8.37)}\]

Apply the bisection method to find the root of \[g(\mu) = \pmb{\rho}^{k+1}(\mu) \cdot \mathbf{V} -

V_0{\qquad(8.38)}\] with \[\rho^{k+1}_j(\mu) = \textrm{clamp}

\left(\hat{\rho}_j^{k+1}, \rho_j^{-,k}, \rho_j^{+,k}

\right){\qquad(8.39)}\] with \[\hat{\rho}_j^{k+1} = \left(\frac{ -

\widetilde{\frac{\partial C}{\partial \rho_j}}}{\mu V_j}\right)^\xi

\rho_j^k.{\qquad(8.40)}\]

Repeat with steps 2-4 until convergence or a maximum number of

iterations is reached.

8.4 Shape optimization

Shape optimization of continua seeks the optimal shape of the outer

perimeter of a structure without adjusting the topology, i.e. without

adding new perimeters like holes. The shape optimization problem for

minimum compliance for a given volume constraint can be formulated

analogously to trusses (see Equation ) as

\[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\mathbf{x}} \quad & C(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{f} \cdot

\mathbf{u}(\mathbf{x})\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & g(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{d} \cdot

\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{x}) - V_0 \le 0 \\

& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X}

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:shape_optimization_continuum}{\qquad(8.41)}\]

A natural choice for design variables are the coordinates of nodes

bounding the meshed domain, just as it has been done for trusses.

However, this leads to jagged meshes with inaccurate stress calculations

and limited deformation capabilities, as illustrated in the following

example.

Example: Direct shape optimization of a cantilever

beam

Consider the cantilever beam from previous examples. If we choose nodal

coordinates of the lower edge as design variables (highlighted with

black dots) and try to minimize the compliance with a volume constraint,

the stiffness improves slightly. However, the mesh is very irregular and

leads to inaccurate stress calculations. Furthermore, the deformation is

limited as it should neither result in collapsed elements nor highly

stretched elements.

We may prevent the disadvantages of the direct nodal optimization by

describing the deformation of the domain by a linear combination of

basic shape modifications. This could be achieved by describing the

perimeter with a spline representation (Christensen and Klarbring 2008) or

by morphing operations on the mesh. Here, we decide to morph the mesh

using radial basis functions (Biancolini et al. 2020). A radial

basis function (RBF) \(\varphi \in

\mathcal{R}\) is a function, that depends on the Euclidean

distance \(r = \lVert

\mathbf{x}-\hat{\mathbf{x}} \rVert\) to some fixed point \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\). We can use radial basis

functions to interpolate the deformation of the mesh for a set of given

control points \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}_i\)

as \[\delta(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{l=1}^P

\gamma_i \varphi(\lVert \mathbf{x}-\hat{\mathbf{x}}_i

\rVert).{\qquad(8.42)}\]

Example: Radial basis functions

Examples for radial basis functions are

Table 8.1

| Gaussian: |

\(\varphi(r) =

e^{-(\epsilon r)^2}\) |

| Linear: |

\(\varphi(r) =

r\) |

The interpolation should coincide with prescribed deformations at the

control points \(\delta_i\), i.e. \[\delta(\mathbf{x}_i) = \delta_i \quad \forall i

\in [1, P]{\qquad(8.43)}\] must hold. To find weights fulfilling

this condition, we can solve the linear system of equations \[\mathbf{M} \cdot \pmb{\gamma} =

\pmb{\delta}{\qquad(8.44)}\] with the interpolation matrix \[M_{ij} = \varphi(\lVert

\mathbf{x}_i-\hat{\mathbf{x}}_j \rVert) \quad i,j \in [1,

P].{\qquad(8.45)}\] Using the control points as design variables,

we can modify the shape smoothly with a linear combination of basic

shape modifications. The type of RBF constraints the solution space of

shapes that can be achieved by shape optimization.

Example: Shape modification with

RBFs

Consider the cantilever beam from previous examples. We can define a set

of shape modifications with control points and Gaussian RBFs. Each shape

modification is defined by its own design variable.

We may also use linear RBFs to define shape modifications:

We may reformulate the optimization problem now in terms of the

design variables \(\delta_i\) as \[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\pmb{\delta}} \quad & C(\pmb{\delta}) = \mathbf{f}

\cdot \mathbf{u}(\pmb{\delta})\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & g(\pmb{\delta}) = \mathbf{d} \cdot

\mathbf{A}(\pmb{\delta}) - V_0 \le 0 \\

& \pmb{\delta} \in \mathcal{D}

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:shape_optimization_morph}{\qquad(8.46)}\]

Just like in shape optimization of trusses, target function and

constraint function are generally non-linear and non-separable. Hence,

we use MMA to approximate the problem and solve it equivalent to

Equations to . We do not elaborate the analytical derivation of the

gradients (this can be found e.g. in Chapter 6.3.2.2 in (Christensen and Klarbring

2008)), but simply rely on automatic differentiation to compute

\(\frac{\partial C}{\partial

\delta_i}\) and \(\frac{\partial

g}{\partial \delta_i}\).

Example: Shape optimization of a cantilever

beam

Consider the truss with Gaussian shape modifications from the previous

example. We select the vertical degree of freedom of the five control

points at the lower edge as design variables \(\pmb{\delta} \in \mathcal{R}^5\).

We want to solve for the optimal shape \(\pmb{\delta}^*\) that minimizes the

compliance of the structure without exceeding the initial volume of the

truss. Hence, we formulate the following algorithm to solve the

approximated problem:

Define the cantilever FEM model with all nodes \(\mathcal{N}\), elements \(\mathcal{E}\), material properties \((E, \nu)\) , volume constraint \(V_0\), design limits \(\pmb{\delta}^-, \pmb{\delta}^+\) and the

initial design choice \(\pmb{\delta}^0\).

Compute the mesh morphing weights given the current design \(\pmb{\delta}^k\) according to \[\pmb{\gamma}^k = \mathbf{M}^{-1} \cdot

\pmb{\delta}^k{\qquad(8.47)}\] and morph the mesh with \[\delta(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{l=1}^P \gamma_i^k

\varphi(\lVert \mathbf{x}-\hat{\mathbf{x}}_i

\rVert).{\qquad(8.48)}\]

Compute the displacements \(\mathbf{u}^k\) by solving the FEM system

for the morphed mesh.

Compute the asymptotes as \(\mathbf{L}^k = \pmb{\delta}^k - s (\pmb{\delta}^+

- \pmb{\delta}^-)\) and \(\mathbf{U}^k

=\pmb{\delta}^k + s (\pmb{\delta}^+ - \pmb{\delta}^-)\) with

\(s \in (0,1)\) during the first two

iterations. In the following iterations, compute the lower asymptotes

according to \[L^k_i =

\begin{cases}

\delta^k_i - s (\delta^{k-1}_i-L^{k-1}_i) &

(\delta_i^k-\delta_i^{k-1})(\delta_i^{k-1}-\delta_i^{k-2}) < 0\\

\delta^k_i -

\frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (\delta^{k-1}_i-L^{k-1}_i) & \text{else}

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.49)}\] and the upper asymptotes

according to \[U^k_i =

\begin{cases}

\delta^k_i - s (U^{k-1}_i-\delta^{k-1}_i) &

(\delta_i^k-\delta_i^{k-1})(\delta_i^{k-1}-\delta_i^{k-2}) < 0\\

\delta^k_i -

\frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (U^{k-1}_i-\delta^{k-1}_i) & \text{else}

\end{cases}{\qquad(8.50)}\]

Compute the move limits as \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{\pmb{\delta}}^{-,k} &= \max(\pmb{\delta}^-, 0.9

\mathbf{L}^k + 0.1 \pmb{\delta}^k) {\qquad(8.51)}\\

\tilde{\pmb{\delta}}^{+,k} &= \min(\pmb{\delta}^+, 0.9

\mathbf{U}^k + 0.1 \pmb{\delta}^k)

{\qquad(8.52)}\end{aligned}\]

Evaluate the gradients of the objective function \(\frac{\partial C}{\partial \delta_i}\) and

the constraint \(\frac{\partial g}{\partial

\delta_i}\) at \(\pmb{\delta}^k\) using automatic

differentiation.

Evaluate the analytical solution \[\begin{aligned}

\hat{\delta}_i(\mu) &=

\begin{cases}

\delta^-_i

&\textrm{if} \quad \frac{\partial

C}{\partial \delta_i} > 0, \frac{\partial g}{\partial \delta_i} >

0 \\

\frac{U_i^k\omega + L_i^k}{1+\omega}, \quad \omega =

\sqrt{-\mu\frac{(\delta_i^k-L_i^k)^2\frac{\partial g}{\partial

\delta_i}}{(U_i^k-\delta_i^k)^2\frac{\partial C}{\partial \delta_i}}}

&\textrm{if} \quad \frac{\partial

C}{\partial \delta_i} > 0, \frac{\partial g}{\partial \delta_i}

<0\\

\frac{U_i^k-L_i^k\omega}{1+\omega}, \quad \omega =

\sqrt{-\mu\frac{(U_i^k-\delta_i^k)^2\frac{\partial g}{\partial

\delta_i}}{(\delta_i^k-L_i^k)^2\frac{\partial C}{\partial \delta_i}}}

&\textrm{if} \quad \frac{\partial

C}{\partial \delta_i} < 0, \frac{\partial g}{\partial \delta_i} >

0\\

\delta^+_i

&\textrm{if} \quad \frac{\partial

C}{\partial \delta_i}< 0, \frac{\partial g}{\partial \delta_i} <

0.

\end{cases} {\qquad(8.53)}\\

\pmb{\delta}^* (\mu) &=

\textrm{clamp}\left(\hat{\pmb{\delta}}(\mu), \tilde{\pmb{\delta}}^{-,k},

\tilde{\pmb{\delta}}^{+,k}\right)

{\qquad(8.54)}\end{aligned}\]

Perform a line search to find the maximum in \[\max_{\mu>0}

\underline{\mathcal{L}}(\mu){\qquad(8.55)}\] with a gradient

decent method. Once again, we may use automatic differentiation to

compute the gradient for the optimization.

Repeat with steps 2-8 until convergence or a maximum number of

iterations is reached.

The following figures show the evolution of the design variables

during the optimization (left) and the final optimized structure (right)

following this procedure.

References

Biancolini, Marco Evangelos, Andrea Chiappa, Ubaldo Cella, Emiliano

Costa, Corrado Groth, and Stefano Porziani. 2020. “Radial Basis

Functions Mesh Morphing.” In Computational Science – ICCS

2020, edited by Valeria V. Krzhizhanovskaya, Gábor Závodszky,

Michael H. Lees, Jack J. Dongarra, Peter M. A. Sloot, Sérgio Brissos,

and João Teixeira, 294–308. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Christensen, Peter W., and Anders Klarbring. 2008. An Introduction to Structural Optimization.

Springer Netherlands.

Eschenauer, H. A., and N. Olhoff. 2001.

“Topology optimization of continuum structures: A

review.” Applied Mechanics Reviews 54 (4):

331–90.

https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1388075.

Harzheim, Lothar. 2014. Strukturoptimierung,

Grundlagen und Anwendungen. Europa Lehrmittle.

Lazarov, B. S., and O. Sigmund. 2011.

“Filters in topology optimization based on Helmholtz-type

differential equations.” International Journal for

Numerical Methods in Engineering 86 (6): 765–81. https://doi.org/

https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.3072.

Sigmund, O. 2007.

“Morphology-based black and

white filters for topology optimization.” Structural

and Multidisciplinary Optimization 33: 401–24.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-006-0087-x.

Sigmund, O., and J. Petersson. 1998.

“Numerical instabilities in topology optimization: A

survey on procedures dealing with checkerboards, mesh-dependencies and

local minima.” Structural Optimization 16: 68–75.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01214002.