4 Optimization using

local approximations

The optimization problems in the previous chapters utilized explicit

functions for the objective functions and constraints. However, in most

practical structural optimization problems, we are not able to formulate

such explicit functions. Instead, we use local approximations as a

remedy. These should be explicit convex functions that approximate the

structural problem in a local region well and are easy to solve at the

same time.

The procedure using a local approximation is as follows:

Choose a starting point \(\mathbf{x}^0\)

Evaluate the target function, constraints and their gradients at

the current position \(\mathbf{x}^k\).

Construct a local, explicit, and convex approximation \(\tilde{f}, \tilde{g}, \tilde{h}\) at \(\mathbf{x}^k\).

Solve the approximated optimization problem to find the next

point \(\mathbf{x}^{k+1}\).

Repeat steps 2, 3, and 4 until you reached a maximum number of

iteration \(k \le N\) or there is no

improvement anymore.

Note that during the optimization within each iteration, we use only

the approximation and do not have to evaluate the expensive target

function.

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter and finishing the exercise, you should be

able to

approximate an optimization problem via Sequential Linear

Programming (SLP)

approximate an optimization problem via Sequential Quadratic

Programming (SQP)

approximate an optimization problem via Convex Linearization

(CONLIN)

approximate an optimization problem via the Method of Moving

Asymptotes (MMA)

discuss the relation between these approximation methods and

chose an appropriate method for a given task

4.1 Sequential linear

programming

In Sequential Linear Programming (SLP), we approximate the functions

in Equation at \(\mathbf{x}^k\) with

first order linear equations \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) &= f(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla

f(\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right)

{\qquad(4.1)}\\

\tilde{g}_i(\mathbf{x}) &= g_i(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla

g_i(\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right)

{\qquad(4.2)}\\

\tilde{h}_j(\mathbf{x}) &= h_j(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla

h_j(\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right)

{\qquad(4.3)}\end{aligned}\] and limit the validity of the

approximation with so-called move limits \[\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{-,k} \le \mathbf{x} \le

\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{+,k}.{\qquad(4.4)}\] The resulting functions

are explicit linear expressions and the set for \(\mathbf{x}\) is compact, hence the

resulting problem is strictly convex. We limit the set because i) the

approximation is only valid close to \(\mathbf{x}^k\) and ii) the linear problem

requires a compact set to be strictly convex.

Example: SLP with move limits

We want to sequentially approximate the following quadratic function

\[f(\mathbf{x})= \mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{Q}

\cdot \mathbf{x} \quad \text{with} \quad \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{R}^2

\quad \text{and} \quad

\mathbf{Q} =

\begin{pmatrix}

2 & 1 \\

1 & 1

\end{pmatrix}.{\qquad(4.5)}\] Obviously, this is

already an explicit convex function and we do not necessarily need to

employ an approximation to minimize a function like this. But for the

sake of this example, we assume that \(f(\mathbf{x})\) is a very complex function

with no explicit expression.

In this case we can get an explicit linear approximation \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = f(\mathbf{x}^k) + 2(\mathbf{Q} \cdot

\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right)

{\qquad(4.6)}\end{aligned}\] with an analytical expression for

the gradient. Then, a first approximation at \(\mathbf{x}^0=(1,1)^\top\) is \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = 3 + \begin{pmatrix} 2\\1

\end{pmatrix} \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k

\right).{\qquad(4.7)}\] Assuming a validity of \(\pm 0.5\) around the approximated point,

the move limits are \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{-,0}=(0.5, 0.5)^\top\)

and \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{+,0}=(1.5,

1.5)^\top\). An optimization with these conditions yields to the

next point \(\mathbf{x}^1=(0.5,0.5)^\top\) with \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = 1.25 + \begin{pmatrix}

1\\0.5 \end{pmatrix} \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k

\right){\qquad(4.8)}\] and with move limits \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{-,1}=(0, 0)^\top\) and

\(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}^{+,1}=(1,

1)^\top\). An optimization under these conditions gives us the

final result \((0,0)^\top\) for the

minimum of the function \(f(\mathbf{x})\). We obtained this by

sequentially employing linear approximations and then performing

optimization on these approximations instead of the original "complex"

and expensive function.

4.2 Sequential quadratic

programming

In Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP), we approximate the

objective function in Equation at \(\mathbf{x}^k\) with second order quadratic

equations \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) =

f(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla f (\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} -

\mathbf{x}^k \right) + \frac{1}{2}\left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k

\right) \cdot \nabla^2 f(\mathbf{x}^k) \cdot \left(\mathbf{x} -

\mathbf{x}^k \right){\qquad(4.9)}\] and the restrictions with

first order linear approximations \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{g}(\mathbf{x}) &= g(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla

g(\mathbf{x}^k) \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right) {\qquad(4.10)}\\

\tilde{h}(\mathbf{x}) &= h(\mathbf{x}^k) + \nabla

h(\mathbf{x}^k) \left(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k \right).

{\qquad(4.11)}\end{aligned}\] This results in a more accurate

approximation and also in a more balanced approximation, i.e. the same

approximation order for the roots of interest (for constraints we are

interested in roots of the function itself, for the objective we are

interest in the roots of the derivative). The Hessian \(\nabla^2 f\) may be approximated

efficiently using the BFGS algorithm. This way, the problem is convex

and we may use the methods from Chapter 3 to obtain the optimum.

4.3 Convex linearization

Both, SLP and SQP, can be applied for any non-linear optimization

problem. However, we can improve the approximation quality

significantly, if we leverage some knowledge about the fundamental

equation types seen in structural optimization.

Let’s consider an assembly of beams and design variables that

describe the cross sectional areas of the beams like in the last example

of Exercise 3. A property like volume or mass is linearly related to the

design variables and a linear approximation would be exact. Conversely,

stress and displacement are related to the inverse of the design

variable and we would need many sequential linear approximations to

approximate the inverse. However, this knowledge suggests that it would

be clever to substitute \(y_j =

x^{-1}_j\), which would lead to a exact approximations for

statically determined truss assemblies (Christensen and Klarbring 2008).

Then, our linear approximation becomes \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = f(\mathbf{x}^k) + \sum_j

\frac{\partial f}{\partial y_j}(\mathbf{x}^k) \left(y_j(x_j) -

y_j(x^k_j) \right){\qquad(4.12)}\] for the objective function,

but obviously the same principles apply for constraints throughout the

remainder of this chapter. Employing the chain rule \[\frac{\partial f}{\partial y_j} (\mathbf{x}^k)

= \frac{\partial x_j}{\partial y_j}(\mathbf{x}^k) \frac{\partial

f}{\partial x_j} (\mathbf{x}^k)

= -(x^k_j)^2 \frac{\partial f}{\partial

x_j}(\mathbf{x}^k){\qquad(4.13)}\] this can be simplified to an

expression without \(y_j\) \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = f(\mathbf{x}^k) + \sum_j

\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}(\mathbf{x}^k)

\underbrace{\frac{x^k_j}{x_j}}_{\Gamma_j} \left(x_j - x^k_j

\right).{\qquad(4.14)}\] The difference to the regular linear

approximation is only the term indicated with \(\Gamma_j\). Hence we can set \(\Gamma_j = 1\) for variables that should be

approximated linearly and set \(\Gamma_j =

x^k_j / x_j\) for variables that should be approximated

inversely. Instead of choosing the approximation for each variable

manually, we may use the the sign of the partial derivative and define

an approximation method as \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) &= f(\mathbf{x}^k) + \sum_j \frac{\partial

f}{\partial x_j}(\mathbf{x}^k) \Gamma_j \left(x_j - x^k_j \right)

{\qquad(4.15)}\\

\Gamma_j &=

\begin{cases}

1 &\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}

(\mathbf{x}^k) \ge 0 \\

\frac{x^k_j}{x_j} &\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial

f}{\partial x_j} (\mathbf{x}^k) < 0.

\end{cases}

{\qquad(4.16)}\end{aligned}\] This method is termed Convex

Linearization or CONLIN (Fleury 1989). The CONLIN method provides

a convex separable optimization problem, hence the Lagrangian duality

method is a suitable solution method (Christensen and Klarbring

2008; Harzheim 2014).

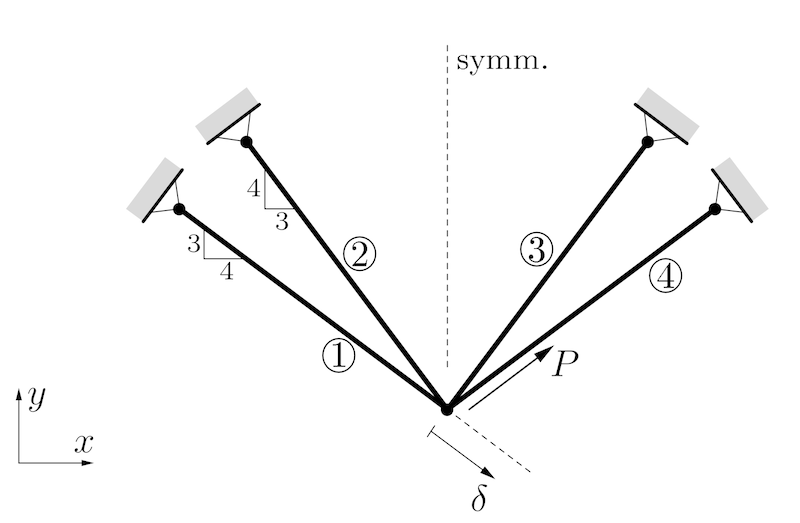

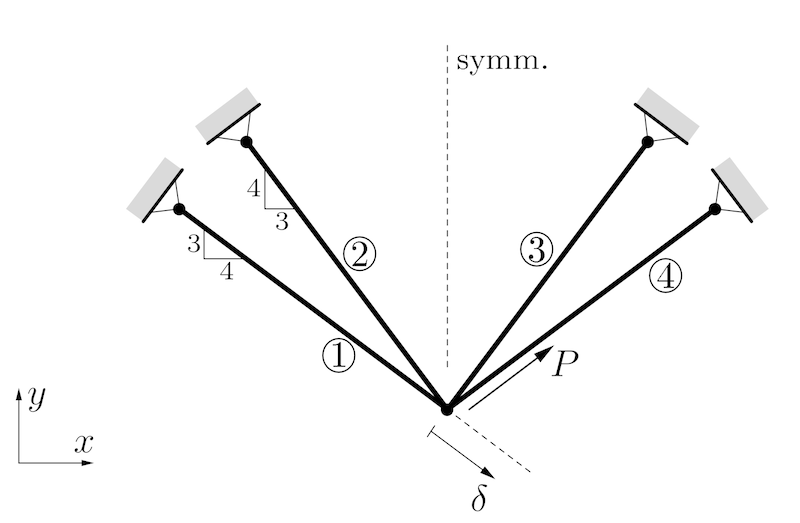

Example: CONLIN

The volume of a four-bar truss (Christensen and Klarbring 2008)

should be minimized under the displacement constraint \(\delta \le \delta_0\). There is a force

\(P>0\) and all bars have identical

lengths \(l\) and identical Young’s

moduli \(E\). The modifiable structural

variables are the cross sectional areas \(A_1=A_4\) and \(A_2=A_3\). We define \(A_0 = Pl / (10\delta_0E)\) and constrain

the variables \(0.2A_0 \le A_j \le 2.5

A_0\). Then we can use dimensionless design variables \(a_1=A_1/A_0 \in [0.2, 2.5]\) and \(a_2=A_2/A_0 \in [0.2, 2.5]\).

The optimization problem is \[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\mathbf{a}} \quad & f(\mathbf{a})= a_1 +

a_2{\qquad(4.17)}\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & g(\mathbf{a}) =

\frac{8}{16a_1+9a_2} - \frac{4.5}{9a_1+16a_2} - \delta_0 \le

0 {\qquad(4.18)}\\

\quad & \mathbf{a} \in [0.2,2.5]^2

{\qquad(4.19)}\end{aligned}\] This problem is not convex,

because the constraint \(g(\mathbf{a})\) (shown as solid black line

in the following plot for \(\delta_0=0.1\)) is not a convex function.

This leads to two local minima, one at \(a_2=0.2\) and one at \(a_2=2.5\).

The CONLIN approximation of the objective function is the objective

function itself - it is already linear. A CONLIN approximation of the

constraint function at \(\mathbf{a}^0=(2,1)^\top\) is computed using

automatic differentiation in PyTorch and results in the dashed black

line. The resulting problem is convex and can be solved, e.g. using

Lagrangian duality. The unique solution of this problem is the point

\(\mathbf{a}^1=(1.2,0.2)^\top\). We can

apply the CONLIN method again at this point to obtain a new convex

problem. Solving this problem gives \(\mathbf{x}^2=(0.85,0.2)^\top\), which is

close to the optimal solution \(\mathbf{a}^*\), but could be improved with

further iterations. Note that not every CONLIN approximation is

conservative, i.e. it can happen that \(\tilde{g}(\mathbf{a}) < g(\mathbf{a})\).

In that case, the solution will tend to oscillate around the optimal

point.

4.4 Method of Moving

Asymptotes

CONLIN is an effective method to turn structural optimization

problems into convex separable optimization tasks. However, it is

sometimes too conservative causing slow convergence or sometimes not

conservative enough causing no convergence at all. We could improve the

method by adjusting how conservative we approximate a function.

We may obtain an adjustable method by defining \[\tilde{f}(\mathbf{x}) = r(\mathbf{x}^k) + \sum_j

\left( \frac{p_{j}^k}{U^k_j-x_j} + \frac{q_{j}^k}{x_j-L^k_j} \right)

\label{eq:mma_start}{\qquad(4.20)}\] where \[\begin{aligned}

p_{j}^k &=

\begin{cases}

(U^k_j-x^k_j)^2 \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}

(\mathbf{x}^k) &\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial

x_j} (\mathbf{x}^k) > 0 \\

0 &\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}

(\mathbf{x}^k) \le 0.

\end{cases} {\qquad(4.21)}\\

q_{j}^k &=

\begin{cases}

0 &\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}

(\mathbf{x}^k) \ge 0 \\

- (x^k_j-L^k_j)^2 \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j} (\mathbf{x}^k)

&\quad \text{if} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_j}

(\mathbf{x}^k) < 0.

\end{cases} {\qquad(4.22)}\\

r(\mathbf{x}^k) &= f(\mathbf{x}^k) - \sum_j

\left(\frac{p_{j}^k}{U^k_j-x^k_j} + \frac{q_{j}^k}{x^k_j-L^k_j} \right)

\label{eq:mma_end}

{\qquad(4.23)}\end{aligned}\] with \(L^k_j < x_j < U^k_j\). The parameters

\(L^k_j\) and \(U_j^k\) are called the lower and upper

asymptotes, respectively. They can be adjusted ("move"), hence the

method is termed Method of Moving Asymptotes (MMA) (Svanberg 1987). It

can be proven that this is a generalization, as setting \(L^k_j \rightarrow 0\) and \(U^k_j \rightarrow \infty\) recovers the

CONLIN method and setting \(L^k_j \rightarrow

-\infty\) and \(U^k_j \rightarrow

\infty\) recovers the SLP method.

To prevent singularities by reaching the asymptotes, we use move

limits \[L^k_j < \tilde{x}_j^{-,k} \le x_j

\le \tilde{x}_j^{+,k} < U_j^k.{\qquad(4.24)}\] similar to SLP.

These could be chosen for example as \[\begin{aligned}

\tilde{x}_j^{-,k} &= \max(x^-_j, 0.9 L_j^k + 0.1 x_j^k)

{\qquad(4.25)}\\

\tilde{x}_j^{+,k} &= \min(x^+_j, 0.9 U_j^k + 0.1 x_j^k).

\label{eq:mma_move_limits}

{\qquad(4.26)}\end{aligned}\]

The advantage of these adjustable asymptotes is that we can bring the

asymptotes closer to the current approximation \(\mathbf{x}^k\) to obtain a more

conservative approximation and move them further away to accelerate

convergence speed. But how do we chose the asymptotes? Svanberg (Svanberg 1987)

suggested the following heuristic approach:

In the first two iterations, set \[\begin{aligned}

L_j^k &= x_j^k - s (x^+_j - x^-_j) {\qquad(4.27)}\\

U^k_j &= x_j^k + s (x^+_j - x^-_j)

{\qquad(4.28)}\end{aligned}\] with \(s

\in (0,1)\).

For the following iterations (\(k>1\)) check for each design variable,

if it oscillates. If it oscillates, i.e. \((x_j^k-x_j^{k-1})(x_j^{k-1}-x_j^{k-2}) <

0\), bring asymptotes closer to \(x_j^k\) by \[\begin{aligned}

\label{eq:mma_heuristic_first}

L_j^k &= x_j^k - s (x_j^{k-1} - L_j^{k-1})

{\qquad(4.29)}\\

U_j^k &= x_j^k + s (U_j^{k-1} - x_j^{k-1}).

{\qquad(4.30)}\end{aligned}\]

If the solution does not oscillate, i.e. \((x_j^k-x_j^{k-1})(x_j^{k-1}-x_j^{k-2}) \ge

0\), move the asymptotes further away from \(x_j^k\) by \[\begin{aligned}

L_j^k &= x_j^k - \frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (x_j^{k-1} -

L_j^{k-1}) {\qquad(4.31)}\\

U_j^k &= x_j^k + \frac{1}{\sqrt{s}} (U_j^{k-1} -

x_j^{k-1}).

\label{eq:mma_heuristic_last}

{\qquad(4.32)}\end{aligned}\]

Svanbergs original version uses the same asymptotes \(L_j^k\) and \(U_j^k\) for the objective function and

constraints. There is also a method termed Generalized Method of

Moving Asymptotes (GMMA) (Zhang and Fleury 1997) that uses

different asymptotes for each function. However, this requires a more

complicated heuristic to obtain such asymptotes.

Example: MMA

Consider the previous example with the optimization problem \[\begin{aligned}

\min_{\mathbf{a}} \quad & f(\mathbf{a})= a_1 +

a_2{\qquad(4.33)}\\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & g(\mathbf{a}) =

\frac{8}{16a_1+9a_2} - \frac{4.5}{9a_1+16a_2} -0.1 \le

0 {\qquad(4.34)}\\

\quad & \mathbf{a} \in [0.2,2.5]^2

{\qquad(4.35)}\end{aligned}\]

A MMA approximation at \(\mathbf{a}^0=(2,1)^\top\) is illustrated in

the following image with the dashed line for \(s_0=0.2\).

If we chose \(s_0=0.5\), we get a

less conservative approximation, as shown in the next image. This

results in faster convergence, as an optimization of the convex problem

gets closer to the optimum in a single step.

This example shows just the first iteration - the full method would

require sequential approximation and optimization with the Lagrangian

duality method until convergence. During each iteration, we would use

the heuristic given in Equations 4.29 to 4.32 to update asymptotes.

References

Christensen, Peter W., and Anders Klarbring. 2008. An Introduction to Structural Optimization.

Springer Netherlands.

Fleury, C. 1989. “CONLIN: An efficient dual

optimizer based on convex approximation concepts.”

Structural Optimization 1: 81–89.

Harzheim, Lothar. 2014. Strukturoptimierung,

Grundlagen und Anwendungen. Europa Lehrmittle.

Svanberg, Krister. 1987. “The Method of Moving Asymptotes—a New

Method for Structural Optimization.” International Journal

for Numerical Methods in Engineering 24 (2): 359–73.

Zhang, Wei-Hong, and C. Fleury. 1997. “A Modification of Convex

Approximation Methods for Structural Optimization.” Computers

& Structures 64 (1): 89–95.